Multimedia Educational Resource Assessment Rubric

Located Educational Resources

The following three multimedia resources were intentionally selected to represent a clear spectrum of quality:

Poor Quality Resource

Biology 1010 Lecture 8: Photosynthesis

- Format: Recorded lecture with a single instructor speaking.

- Visuals: Dense on-screen text, minimal diagrams and animations.

- Interaction: None, purely passive viewing.

- Presentation Style: Linear, lecture-driven; little variation in pacing or delivery.

- Audience Engagement: Low with no prompts, questions or feedback.

Okay/Good Quality Resource

Photosynthesis: Crash Course Biology #8

- Format: Short instructional video with narration and visuals.

- Visuals: Simple diagrams, step-by-step explanations.

- Interaction: Limited to pausing, replaying or following along with examples.

- Presentation Style: Structured, segmented content and clear progression.

- Audience Engagement: Moderate level of engagement with visual support aids understanding but limited active participation.

Excellent Quality Resource

PhET Interactive Simulation: “Greenhouse Effect”

Access simulation through this link: https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulations/greenhouse-effect

- Format: Web-based interactive simulation.

- Visuals: Dynamic, real-time visual representation of photosynthesis processes.

- Interaction: Learners manipulate variables and immediately see effects.

- Presentation Style: Exploratory, learner-directed and flexible pacing.

- Audience Engagement: High level engagement encourages experimentation, observation and discovery.

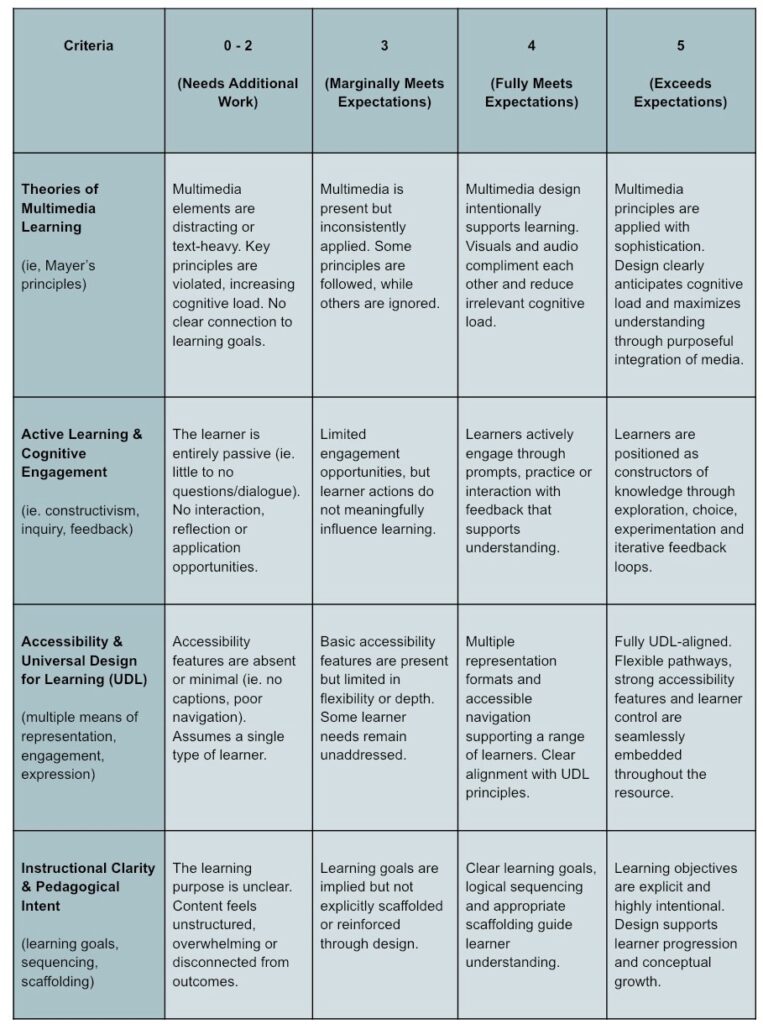

Evaluation Using the Multimedia Assessment Rubric

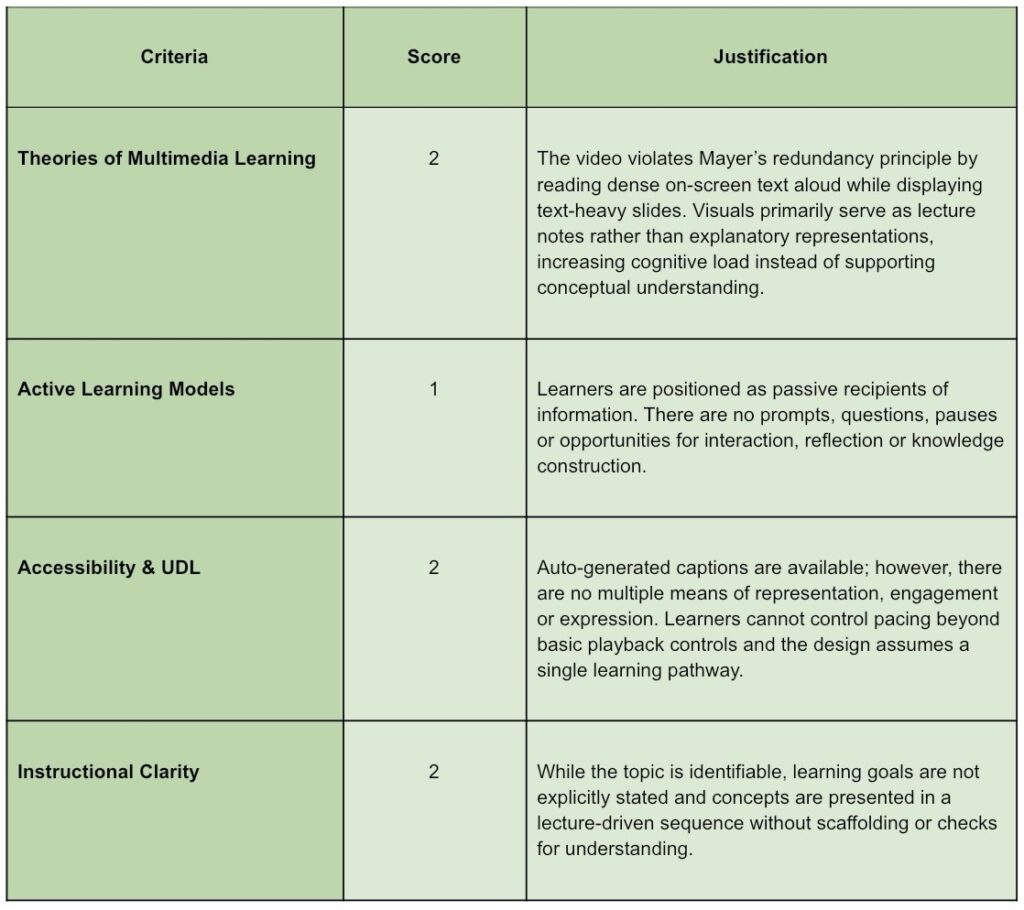

Resource 1: Poor Quality

Overall Evaluation:

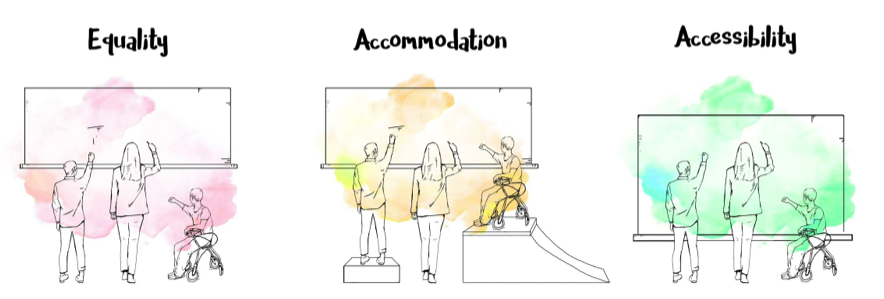

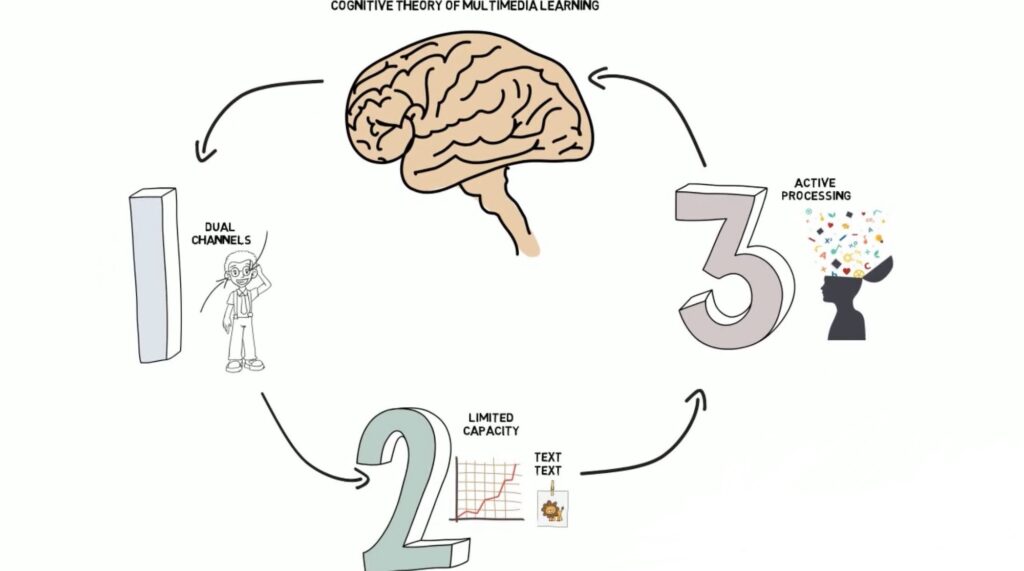

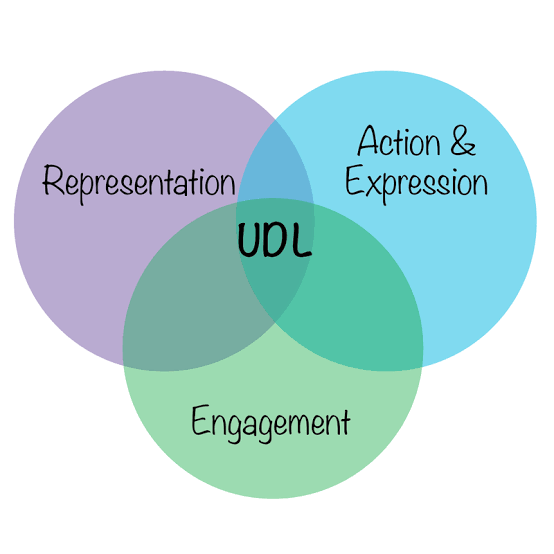

This resource reflects a transmission-based approach to learning and demonstrates limited awareness of multimedia learning theory, active learning models or UDL principles.

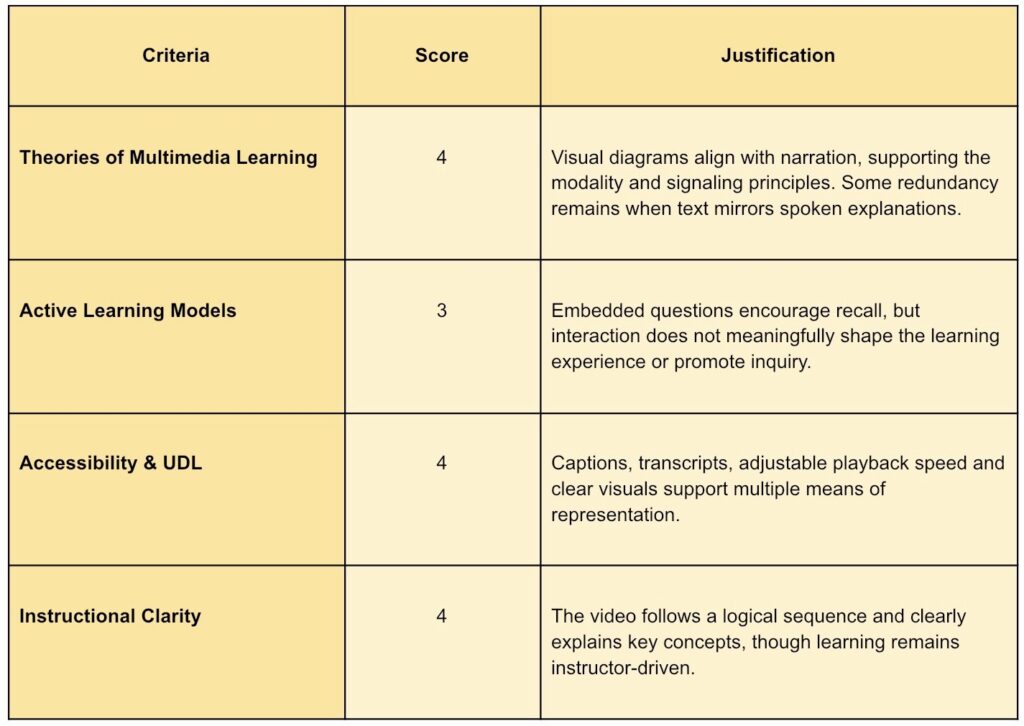

Resource 2: Okay Quality

Overall Evaluation:

This resource demonstrates strong alignment with multimedia learning theory and accessibility practices but only partially engages learners in active meaning-making.

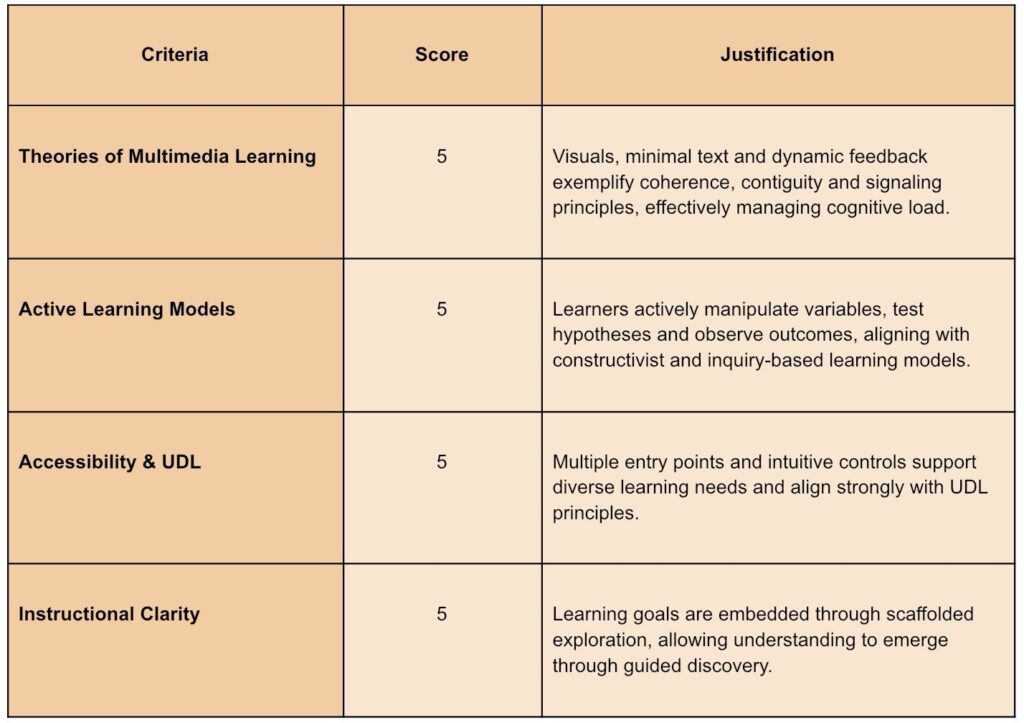

Resource 3: Excellent Quality

Overall Evaluation:

This resource represents excellent practice in multimedia instructional design by seamlessly integrating theory, accessibility and active learning into a cohesive learner-centered experience.

Resources

BioProfessor101. (2017, January 27). Biology 1010 lecture 8: Photosynthesis. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=33PsCr15T9o

CrashCourse. (2012, March 19). Photosynthesis: Crash Course Biology #8. YouTube.

PhET Interactive Simulations, University of Colorado Boulder. (n.d.). Greenhouse Effect: Interactive simulation.