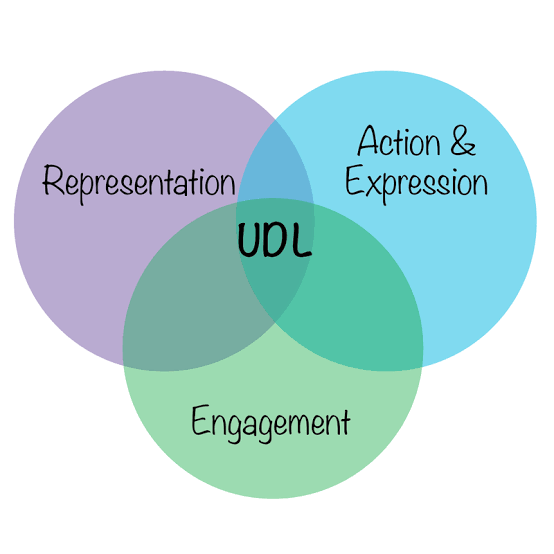

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that helps educators design curriculum with learner variability in mind by offering multiple means of engagement, representation and expression (CAST, 2014). Rose, Meyer, and Gordon (2014) emphasize that learning differences are normal, not exceptions and that barriers exist in curriculum design, not in students. This idea has shifted how I approach teaching. During my practicum, I noticed lessons ran more smoothly when I gave students multiple entry points, through visuals, hands-on tasks or oral explanations. In an online context, this could look like providing transcripts with videos, using graphic organizers or offering choices in how students demonstrate their understanding. UDL reminds me that flexibility is an important form of equity.

This video highlights these ideas, which shows how intentional design can open up learning for all students.

Inclusive Learning Design

Inclusive Learning Design: This focuses on creating learning environments that prioritize equity, belonging and representation. It builds on UDL but goes further by focusing on equity, belonging and representation. It ensures that learners not only have access but also see themselves reflected in the curriculum and feel valued in the learning community. The BC Ministry of Education (2019) highlights the importance of representation in creating inclusive environments. I have tried to put this into practice by using picture books that reflect diverse cultural identities during early literacy lessons. In digital spaces, I imagine extending this by incorporating examples, images and case studies that highlight a range of voices and perspectives. For me, inclusion means that every learner feels both represented and respected.

Synchronous and Asynchronous Learning

Both synchronous and asynchronous formats play a valuable role in supporting diverse learners. Synchronous learning involves real-time interaction, such as Zoom classes or live discussions, which foster immediacy and community. Asynchronous learning, in contrast, allows learners to engage on their own schedule through tools like discussion boards, recordings or independent projects. This provides flexibility but requires careful design to maintain engagement (Hrastinski, 2008).

From my own experience, synchronous sessions have helped me feel connected to peers and instructors, while asynchronous options gave me the time I needed to reflect and process ideas. In my teaching, I plan to blend these approaches, for example, beginning with a live discussion and then extending it through reflective online activities. This balance allows students with different needs, schedules or processing speeds to participate fully.

Community of Inquiry & Effectively Online Education

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework outlines three key elements for effective online learning: teaching presence, social presence and cognitive presence (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000). Teaching presence comes from clear design and facilitation, social presence from building trust and interaction and cognitive presence from supporting reflection and sustained discourse.

I’ve experienced how powerful these elements can be. In courses with clear structure and instructions, I was able to focus on learning instead of logistics. When instructors provided timely feedback, I felt more connected, which increased motivation. In my practicum, I also noticed that when students engaged in dialogue with peers, their ideas became deeper and more collaborative, reflecting cognitive presence.

Closing Reflection

Module 3 reminded me that inclusion is not about adding extra supports but about designing from the beginning with variability, equity, and connection in mind. Moving forward, I want to bring UDL and inclusive design together with a thoughtful balance of synchronous and asynchronous learning, while using the CoI framework to strengthen presence and belonging. My goal is to create learning environments where all students feel capable, cared for and connected.

References

BC Ministry of Education. (2019). British Columbia curriculum. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous and synchronous e-learning. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 31(4), 51–55. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2008/11/asynchronous-and-synchronous-elearning

Rose, D. H., Meyer, A., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Seeing UDL in action in the classroom. (2012, November 15). [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/hCHTxTfkBsU