Rethinking What Accessibility Really Means

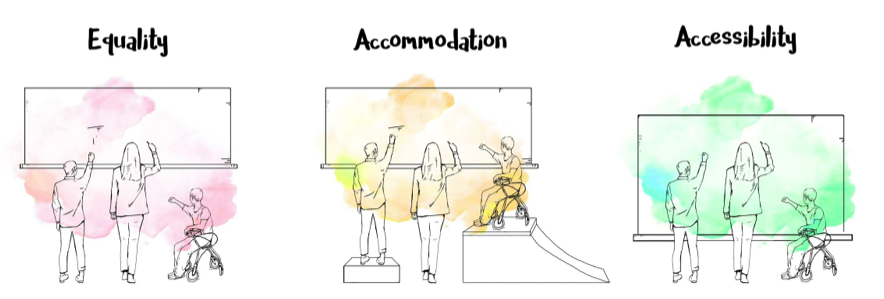

Accessibility in education is often framed as something we add after a problem shows up, an accommodation, a workaround, a special support for a few learners. Exploring and reflecting on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and inclusive design has pushed me to rethink that idea entirely. Accessibility isn’t reactive, it’s intentional. It’s about designing learning experiences from the start with the understanding that learners are diverse in how they think, process, move and engage.

When barriers exist, they’re often not about a learner’s ability, but about a mismatch between people and the environments they’re expected to learn in. When those environments are designed more thoughtfully, many barriers fade away or never appear in the first place.

Accessibility as a Foundation for Inclusion

This way of thinking connects closely to the social model of disability and the core principles of UDL: multiple means of engagement, representation and expression. What feels most affirming about UDL is how familiar it is. The strategies UDL promotes (choice, flexibility, varied ways of showing understanding) are already hallmarks of good teaching.

For example, a TEDxTalk on the power of inclusive education illustrates how classrooms can be structured so that all learners actively participate, contribute and support one another’s thinking, modeling the kind of collaborative, student-centered engagement that active learning aims to promote. When students can access content in different ways and express their learning through multiple formats, participation increases across the board. Accessibility doesn’t single students out or label them as needing something “extra.” Instead, it creates learning conditions where more students can succeed without having to ask for special support.

Designing Accessible Multimedia

Accessibility becomes especially important when learning shifts into multimedia and interactive spaces. While multimedia can be engaging and powerful, it can also create barriers if meaning is locked into a single sensory channel. One key takeaway from the Accessible Multimedia reading was that accessibility isn’t about stripping media of creativity, it’s about expanding how meaning is communicated.

Captions, transcripts and audio descriptions are often thought of as niche supports, but they benefit far more learners than we tend to realize. English language learners, students processing dense information or anyone who prefers reading along while listening all benefit. Clear layout, thoughtful pacing and reduced cognitive load also make multimedia experiences more welcoming and easier to navigate.

Inclusive Design in Practice

Inclusive design asks us to design with difference as the norm, not the exception. There is no “average” learner and once that idea is let go, lesson planning starts to shift. Rather than asking who might struggle, I find myself asking how learning can offer multiple entry points from the beginning.

This shift feels both challenging and reassuring. It challenges habits rooted in one-size-fits-all thinking, but it also aligns closely with my experiences using UDL-informed strategies in inclusive classrooms.

Beyond the Visual

Because graphic design is so visually driven, it can unintentionally exclude learners if information is communicated only through images or colour. Pairing visuals with clear text, consistent layouts, strong contrast and audio explanations makes content more accessible for learners with visual impairments and often clearer for everyone else.

Accessibility is Just Better Design

Ultimately, accessibility and UDL push educators and designers toward learning environments that are flexible, thoughtful and human-centered. When accessibility is treated as a foundation rather than an add-on, it leads to better design, design that acknowledges and supports the many ways learners engage with the world.