Rethinking Multimedia in Educational Design

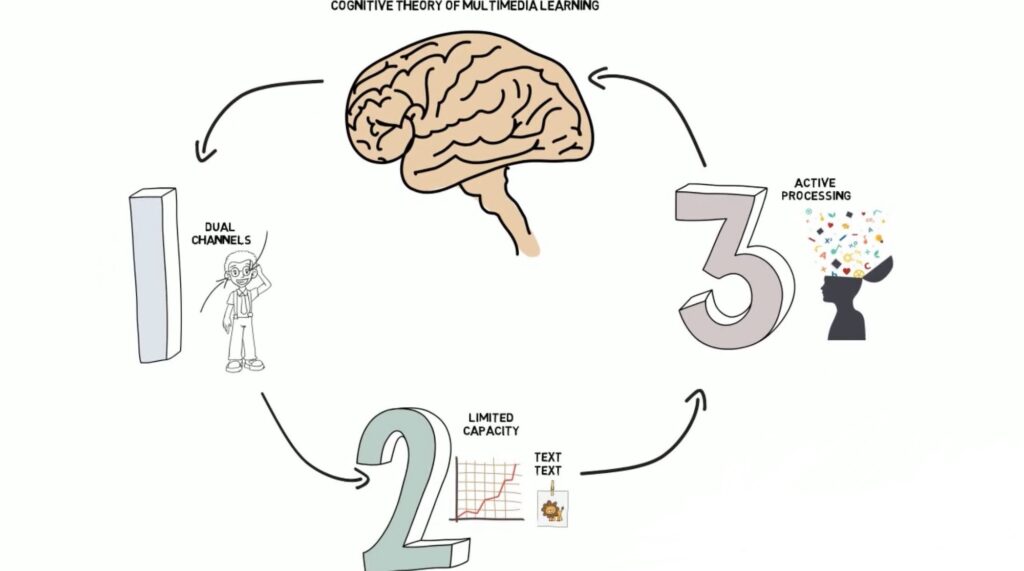

The theories of multimedia learning explored in this module have genuinely shifted how I think about educational design. Rather than asking which tools or platforms are the most engaging, these readings pushed me to focus on how learners process information and why certain combinations of text, images and audio work better than others. The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML) offers a powerful framework for understanding learning at a neurological and cognitive level, reminding designers that more media does not automatically lead to better learning.

When Less Really Is More

Several of the principles immediately felt intuitive based on my own experiences as both a learner and a developing educator. The coherence principle, which emphasizes removing extraneous material, resonated strongly. I have often felt overwhelmed by slides or online modules filled with decorative images, background music or dense blocks of text. Learning that these elements compete for limited working memory helped validate why simpler, more focused designs often feel clearer and more effective.

The signaling principle also felt familiar. Headings, arrows and visual emphasis have always helped me identify what matters most and how ideas connect. Seeing this instinct supported by cognitive theory helped me recognize these strategies as intentional design choices rather than just personal preferences.

Confronting the Limits of Cognitive Load

What surprised me most was the strict limitation of cognitive capacity described in CTML. I had previously assumed that motivated learners could adapt to complex or overloaded presentations. The readings challenged this assumption, emphasizing that even highly engaged learners can struggle when cognitive load is poorly managed.

The split-attention effect, in particular, made me reflect on how often text and images are separated across slides or webpages. When learners have to constantly shift their attention to mentally integrate information, valuable cognitive energy is lost, often without designers realizing it.

Learning from Social Media Design

Interestingly, social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok demonstrate how effective multimedia design can be when text and visuals are intentionally aligned. Short captions, strong visual focal points and minimal on-screen text closely reflect CTML principles such as coherence and signaling, even though the primary goal is engagement rather than learning. Embedding screenshots or short video examples from these platforms could be a useful way to illustrate how multimedia principles show up in familiar, everyday contexts.

Reflecting on My Own Learning Habits

I also realized that I have intuitively followed the dual-coding principle when taking notes by doodling diagrams, symbols and visual metaphors alongside written text. This approach supports deeper understanding and synthesis rather than passive transcription. At the same time, I noticed that I haven’t always applied the coherence principle in my own teaching materials, often adding extra text “just in case.” Moving forward, I want to be more intentional by asking whether each element directly supports the learning goal.

Designing with Cognitive Care

When I imagine creating educational content for my own projects, I now picture learners who may already feel cognitively overloaded. This perspective encourages me to prioritize clarity, pacing and accessibility. Principles such as modality, spatial contiguity and segmenting feel especially important, though challenging, because they require letting go of the urge to include everything at once.

By incorporating diagrams, short videos and annotated visuals thoughtfully rather than decoratively, I can design multimedia experiences that truly support learning rather than distract from it.